The Path to Go-to-Market Fit

Getting to go-to-market fit requires teams to navigate enormous complexity under uncertainty through a mix of top-down guidance and bottom-up experimentation

Hey! It’s Andreas from Monetisation Matters, the home of in-depth articles and actionable insights on Strategy and Monetisation. Built for Founders, Product, and Product Marketing leaders as they navigate their $1m to $100m growth journeys. This month’s article looks at getting to go-to-market fit, why the odds are stacked against you, and how to reduce complexity down, through a mix of bottom-up experimentation and structured top-down decision making.

How to think about fit

The transition between the initial success of founder-led sales and a repeatable engine of growth is when many start-ups get stuck. The potential from having achieved a degree of product-market fit does not translate into revenue. So much promise. Wasted.

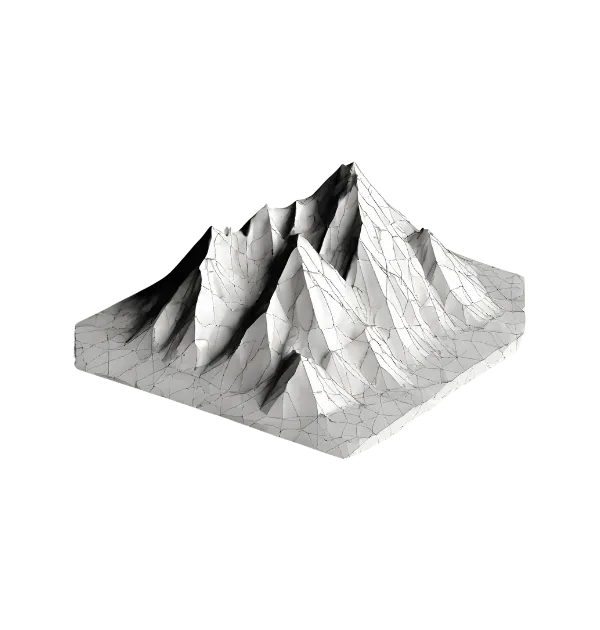

The gap looks small but it’s a chasm – much harder to cross than it seems. Founders and their teams need to build the machine that will deliver growth, whilst hitting ambitious revenue targets quarter-on-quarter. They fly the plane whilst trying to build it. ‘Fitness’: the relationship between the business and the market is in large part what will drive the revenue outcomes they are looking for. A way to visualise what’s going on is to use a fitness landscape. Every point on the landscape is a particular strategy and configuration of the business, where height represents outcomes.

A small adjustment to coordinates on the landscape can equate to a large change in height. Fitness is sensitive to small changes in your go-to-market strategy, whether that is adjusting your ICP, messaging, resourcing, and so on. If you knew what the landscape looked like, you could design your strategy and configure the business in a way that would maximize fit. But you don’t. Building up an understanding of your customers, what they want and how they buy, helps to bring some clarity – but decisions are still made under uncertainty. The path forward is rarely obvious.

Good mistakes, and bad mistakes

Strategy isn’t top-down or bottom-up; it’s both. Top-down decisions primarily drive focus and knock out what not to do. It sets boundaries around where on the landscape the business should play. This can also be informed bottom-up. As more of the landscape is explored, more of the landscape can be ruled out.

This bottom-up search process isn’t sophisticated and it doesn’t need to be. The reality is that teams use simple heuristics to make progress – they try new things, stop doing the things that don’t work, and do more of what does. Thousands of small steps forward. The path to go-to-market fit is one of continuous learning and refinement. Taking steps in the wrong direction is part of the process – your path to go-to-market fit has to have a high tolerance for errors. It’s what fuels the learning process. Making mistakes is a feature, not a bug.

At the same time, Series A startups are, in particular, severely resource constrained and may only have 18 months of runway before they need to raise more capital. They can’t afford to make more than one or two big mistakes. This seems at odds with ‘mistakes that are needed to fuel learning’. What matters are the types of ‘mistakes’. Low consequence errors that teach you something are helpful. Betting the farm on what ends up being the wrong direction is not. Bottom-up experimentation provides a lot of the insight needed to make those bigger top-down bets. Accountability for those bigger bets sits with founders to get right, whether they have expertise in the topic area or not.

More complexity than you could ever handle

I believe there are three high-level dimensions to go-to-market fit that founders and their teams need to get right.

Orientation: where in the market they will focus their efforts.

Systems: how they will find demand and translate it into paying customers.

Resources: how they will allocate resources (people and capital).

Orientation requires decisions over how to segment the market and then which segments to pursue. Do you segment by industry, size, use case, region, etc.? Then, which of those segments will you orient the business around, which companies, departments and personas will you target. At the same time you are building the machine – making decisions over channels, qualification frameworks, sales and marketing technology stack, and so on. Finally you deploy headcount and capital in the right places.

Below is a relatively simple option space that shows the number of options that could form the basis of a go-to-market strategy. For example: six ways to segment the market, four channels to market, etc. The size of the option space – equivalent to coordinates on our fitness landscape – is calculated by multiplying the different options across variables. The example below equates to 1.8M coordinates. 1.8M different ways to configure the business. That should be sobering. That’s the level of complexity a business navigating to go-to-market fit needs to contend with.

For all practical purposes, the chances that a team gets lucky and designs the optimal strategy are zero. Wandering the landscape, making small adjustments, isn't going to allow teams to learn and adjust fast enough before running out of runway. How is it possible that any business, facing these sorts of odds, gets it right?

Cut complexity in half, again and again

We need a way to radically reduce the 1.8m possibilities to have any chance of making progress. Every decision can be restated as a go/no-go decision. This is represented by taking the log base 2 of each variable and summing the results. In this case 22. The magic of this approach is that it reduces an option space of 1.8m coordinates to just 22 go/no-go decisions. That starts to sound much more doable.

22 decisions represent the maximum complexity we need to manage. In reality, many of these decisions will be interdependent. For example, choosing to focus on a particular segment might eliminate several personas that aren’t relevant. Mapping out interdependencies reduces the number of go-to-market designs that make sense in reality. For example, you aren’t going to hire enterprise account executives if your acquisition motion is product-led. That would be insane.

A massive reduction in complexity is driven by your choice of customers. That decision has a bunch of knock-on effects on the remaining decisions. Not committing to a section of the market to fight for is so damaging because it retains enormous complexity. Not only are you failing to reduce the option space, but you will also need to build more internal capabilities to satisfy very different fitness conditions between segments. For example, if you choose to serve large enterprises and a prosumer segment, you are going to need to build two completely different sets of capabilities.

Where does this leave us? Getting to go-to-market fit, developing a strategy in general, involves navigating complexity under uncertainty. Significantly more complexity than is generally recognised as I demonstrated with the option space above. To have any chance of succeeding founders and their teams need to:

Narrow down their ICP as much as possible to drive focus;

Map out the consequential decisions they need to make and their interdependencies;

De-risk those decisions through small scale testing before making large costly bets;

Keep the main thing the main thing - avoid distractions (which have an outsized impact on complexity).

I enjoy writing, but it is a tremendous investment. If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it with your colleagues and friends so that it may grow.

Thank you.

Great stuff, Andreas. In case it helps anyone else: ICP = Ideal Customer Profile.