The Viable System Model

An introduction to a universal blueprint of how businesses must organise to survive and thrive

Hey! It’s Andreas from Monetisation Matters, the home of in-depth articles and actionable insights on Strategy and Monetisation. Built for Founders, Product, and Product Marketing leaders as they navigate their $1m to $100m growth journeys. This article explores at the Viable System Model, a powerful yet largely unknown tool to understand how companies really organise, diagnose what may be going wrong, and design something better.

What makes a business viable?

I can’t remember how I came across Stafford Beer and his Viable System Model (VSM), probably after reading about something equally esoteric. The model’s power is rivalled only by its obscurity. It is the product of asking “what needs to be true for a system to be viable”, where viability is defined as a system’s ability to survive (and thrive) in a changing environment.

“To succeed you must first survive.”

Warren Buffet

Beer studied the central nervous system to derive a model for viability. Humans have proven they are capable of surviving in a changing and hostile environment over a 300,000 year period. There must be some deep wisdom encoded within us that we can learn from and then abstract to complex systems generally — including for our purposes, business. That is what Beer accomplished.

“Nature has generated by evolution the best control system for complex environments”.

Stafford Beer

The Viable System Model

VSM is a map of how businesses must organise to remain viable — like all maps, it isn’t true in that a map is not the landscape — but it is useful. Now that I have this mental model implanted in my head it’s become much faster and easier for me to diagnose sources of dysfunction in the businesses I support, and identify potential remedies.

The reason VSM isn’t widely known isn’t due to a lack of usefulness: when you read Stafford’s work — or try to interpret his diagrams — your head explodes from the complexity. Unfortunately, he did not make his gift to the world easy to comprehend. It’s a damn shame, because after spending a year trying to get my head around it, I am now convinced of it’s genius. Just as the bow-tie model is now ubiquitous among GTM teams, VSM should be familiar to every manager and leader, of every organisation, no matter the size.

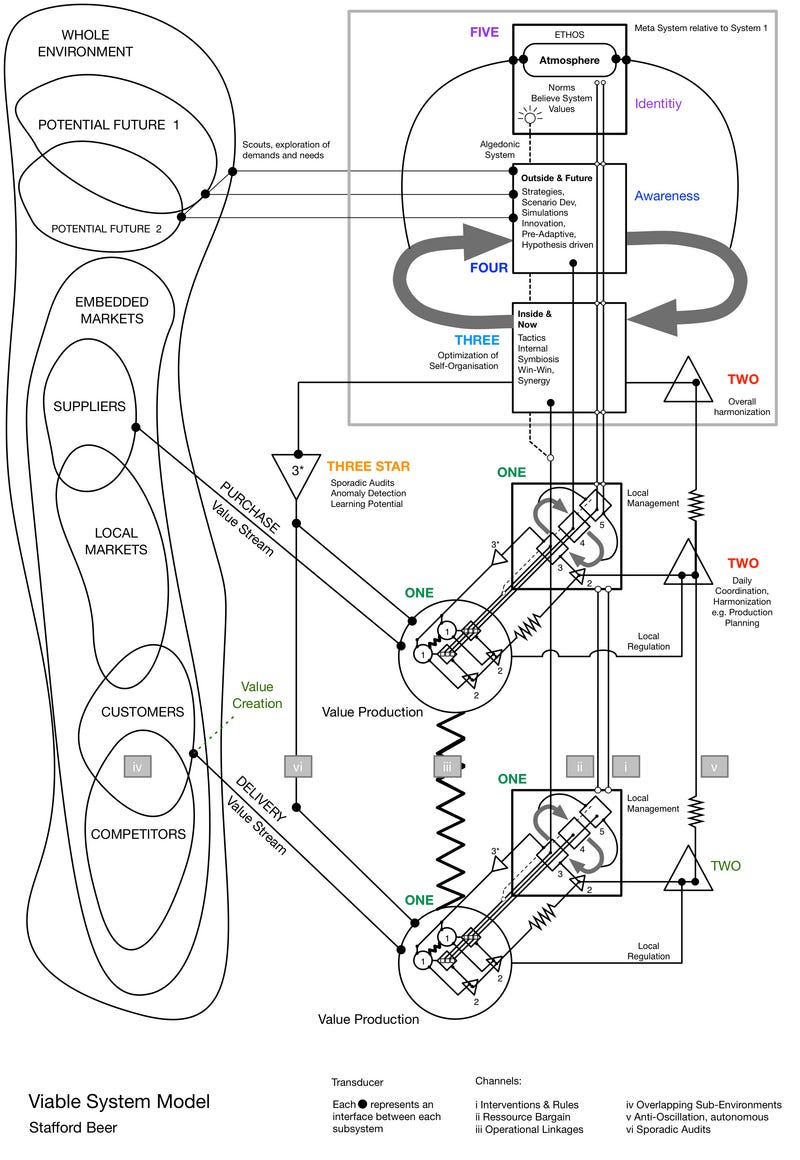

A schematic of VSM — a great way to scare people off investigating further.

When you strip away the complexity, it’s relatively simple. Maybe I couldn’t explain it to a five-year-old, but I think a ten-year-old could grasp the crux of it. Before walking through the actual model, it’s useful to start with what needs to be true for a business to survive over time.

Purpose. The purpose of a business is what it does. It will change what it does to ensure its survival. Survival is more important than continuity of purpose.

Change. To stay useful, it has to keep an eye on what is happening in the environment. Do customers still want what it’s selling? Based on what it observes and anticipates, it decides how to develop and adapt to ensure its survival.

Management. Whatever it does, it needs to do well given its limited resources. It also wants to check that the activities it believes are happening, are in fact happening.

Coordination. No business depends only on the actions of one individual, so it must ensure that activities, individuals, and teams are coordinated.

Execution. The actual work must get done: writing lines of code, calling prospects, onboarding customers, etc.

Information. Finally, all of this can only happen if the right information flows to the right place, at the right level of detail, and with the right frequency.

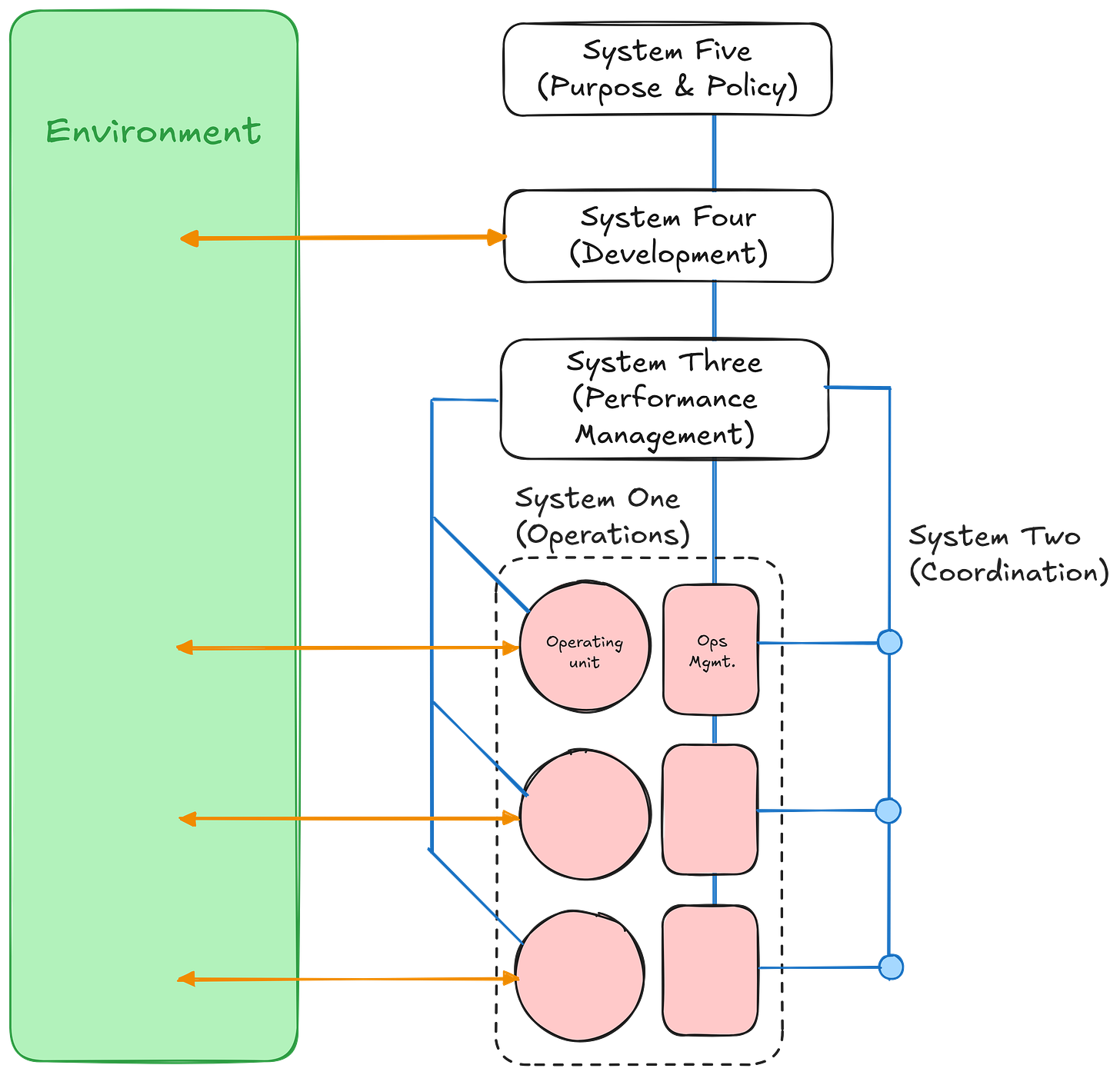

If we work back from these ‘requirements’, we get the VSM. It is organised into five sub-systems. System One is the lowest level of the hierarchy and System Five is the highest. System One is not the most ‘junior’ and System Five the most ‘senior’ — it is not equivalent to moving up an org chart.

One source of VSM’s power is its applicability at different scales, whether that is at the level of an individual, team, function, business, industry, or even the economy as a whole as Beer attempted with the Chilean economy and his ‘Project Cybersyn’. VSM is recursive because organisations are recursive: individuals sit within teams, which sit within departments, which sit within business lines, and so on.

What is included in each subsystem depends on what you are looking at. If you were to apply VSM to the entire business, the Sales function would be a System One operating unit. You could also treat the Sales function as the system, in which case a BDR team would be an operating unit.

System One (Operations): the primary operations of the business or department you are looking at. For example, Sales or Engineering functions when applied to a SaaS business. Back office and support functions wouldn’t count as a primary activity as no SaaS business exists to do accounting — finance exists to support the management or development of System One activities.

System Two (Coordination): how activities stay coordinated, keeping operations within a sensible range by avoiding wild oscillations, resolving conflicts, and standardising operating procedures. This could be accomplished through a mix of people, process and technology. Tools for coordination can and often are simple, for example a shared calendar.

System Three (Performance Management): manages System One operating units and the here and now. It sets performance expectations, allocates resources, optimises existing processes, and evaluates and rewards performance. It manages the balance between operating units acting as a cohesive whole while maintaining their autonomy. System Three also drops down occasionally to engage with System One operating units directly to: i) verify information it is getting through official reporting channels; and ii) develop a better understanding of what is happening on the ground.

System Four (Development): where the business looks out at what is changing in the environment, what may happen in the future, and determines how it might need to adapt. Scenario planning, R&D, marketing, and experimentation are all examples of System Four activities.

System Five (Purpose & Policy): where mission, vision, values, structure, and overall policy is set. It makes the major strategic decisions and manages the balance between preparing for the future (System Four) and delivering on the here and now (System Three).

Information Flow: across all systems are appropriate flows of information from the environment, across individuals, teams and functions, up towards the Board, and then back down again — delivered through a mix of people, process and technology.

Coping with variety

Ashby’s law sits at the heart of VSM: “only variety absorbs variety”. Simply, organisations need to be sufficiently complex to cope with a complex environment, and managers need a sufficient range of responses to match the complexity of the organisation they are trying to control.

Managers, functional leaders, and CEOs are not superhuman — they need to find ways to amplify their own variety, and reduce incoming variety, so that they can cope with the situations beings thrown at them.

“Any color as long as it’s black.”

Henry Ford

Ford relied on reducing incoming variety rather than amplifying the variety of his workforce. His philosophy was to “get it right, and keep it the same’ which allowed him to simplify and optimise operations, adopting a command and control approach to management. It worked because he was able to keep variety between Ford, and the market, and across operations in balance through standardisation. That doesn’t mean the market had low variety, it didn’t, and explains why there was a large aftermarket of businesses supplying various enhancements and customisations to the Model T. Other businesses stepped in to absorb variety of the market that Ford did not want to address.

Minimising incoming variety is still as relevant as it was in the 1920s especially for resourced constrained startups, however, customers are more demanding, competition is more intense, and employees want more than just a paycheck. So there is an avalanche of complexity that needs to be dealt with, and more importantly things just move faster today, so there’s a need to be more adaptable. Internal variety needs to be increased just as much as incoming variety needs to be reduced.

One of the most effective ways to amplify internal variety is to provide autonomy, whether that is at the level of an individual, or operating unit. The people doing the work, who are in the direct flow of information are best placed to make good decisions quickly. If every decision needed to be kicked up the chain of command, progress would grind to a halt. At the same time if everyone were provided maximal autonomy it would obviously be chaotic. VSM acknowledges that organisations need both, there must be space for autonomy, and operating units must also act cohesively through coordinating mechanisms, and through a well functioning System Three.

How to start using VSM

The immediate benefits of VSM without needing to be an expert in it (in my opinion) is to use it as a diagnostic tool to quickly identify sources of dysfunction and gaps in capability. I’ve listed out a number of key questions that I now use when working with Notion’s portfolio.

Are individuals clear on what their job actually is, and what activities are expected of them every day, week, and month?

Are activities and teams coordinated?

Do we have the right metrics and visibility across teams to manage performance in the here and now?

Have the targets we’ve set reflect the resources we have equipped operating units with?

Do we have the information (both internal and external) we need to make the decisions we want to make?

Are managers conducting skip level meetings, and diving deeper into the business to validate reporting and learn from the ‘factory floor’?

Have we got the right balance of focus and investment between managing the here and now vs. developing for the future?

Do we have a strong purpose which orientates the business, is well understood across the business, and guides decision making in the absence of explicit instructions?

This has only been a short intro to VSM which has significant depth not captured here — I hope though it has inspired you to dig deeper and unlock the benefits for your business.

I enjoy writing, but it is a tremendous investment. If you enjoyed this article, please consider sharing it with your colleagues and friends so that it may grow.

Thank you.